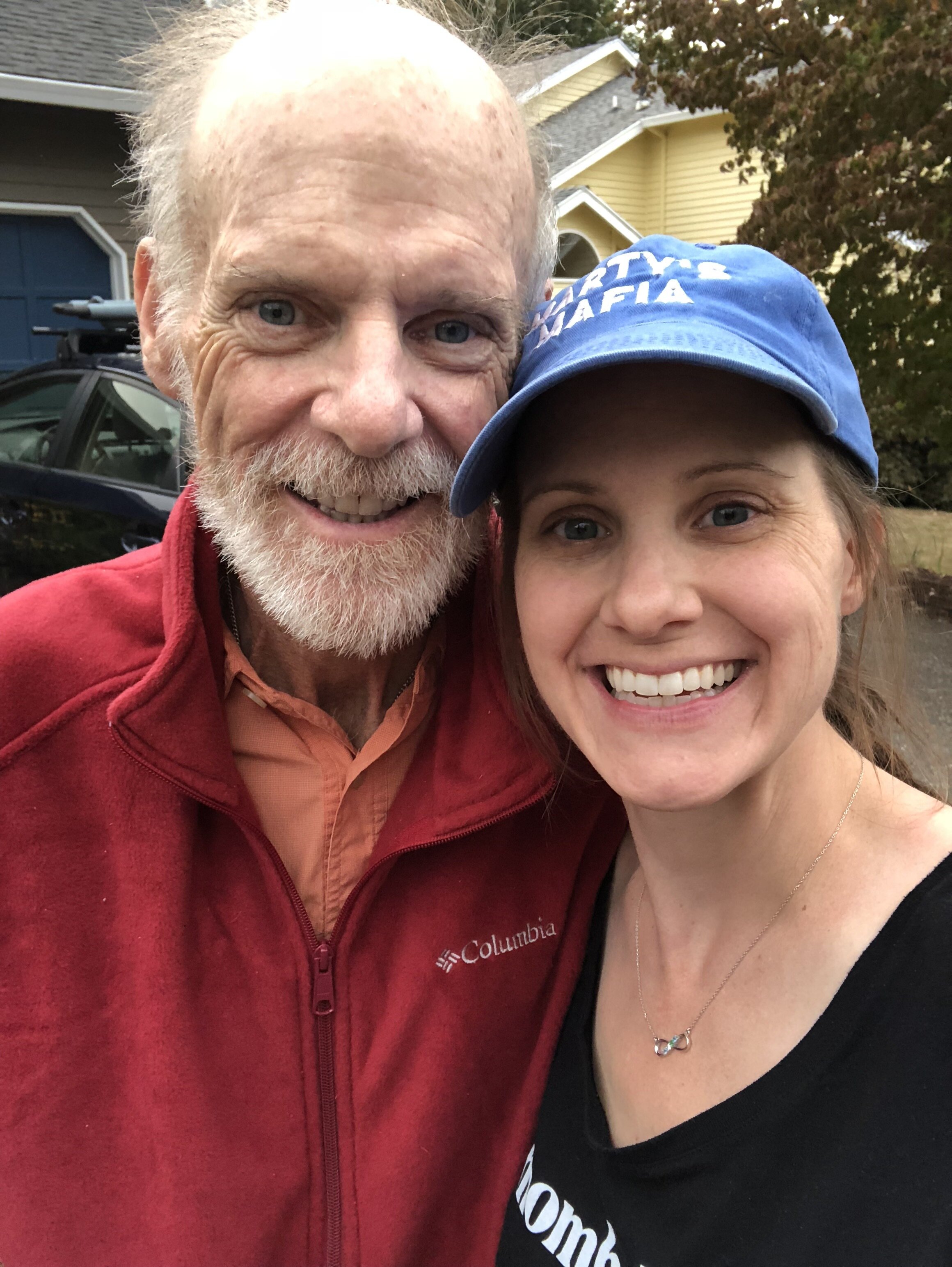

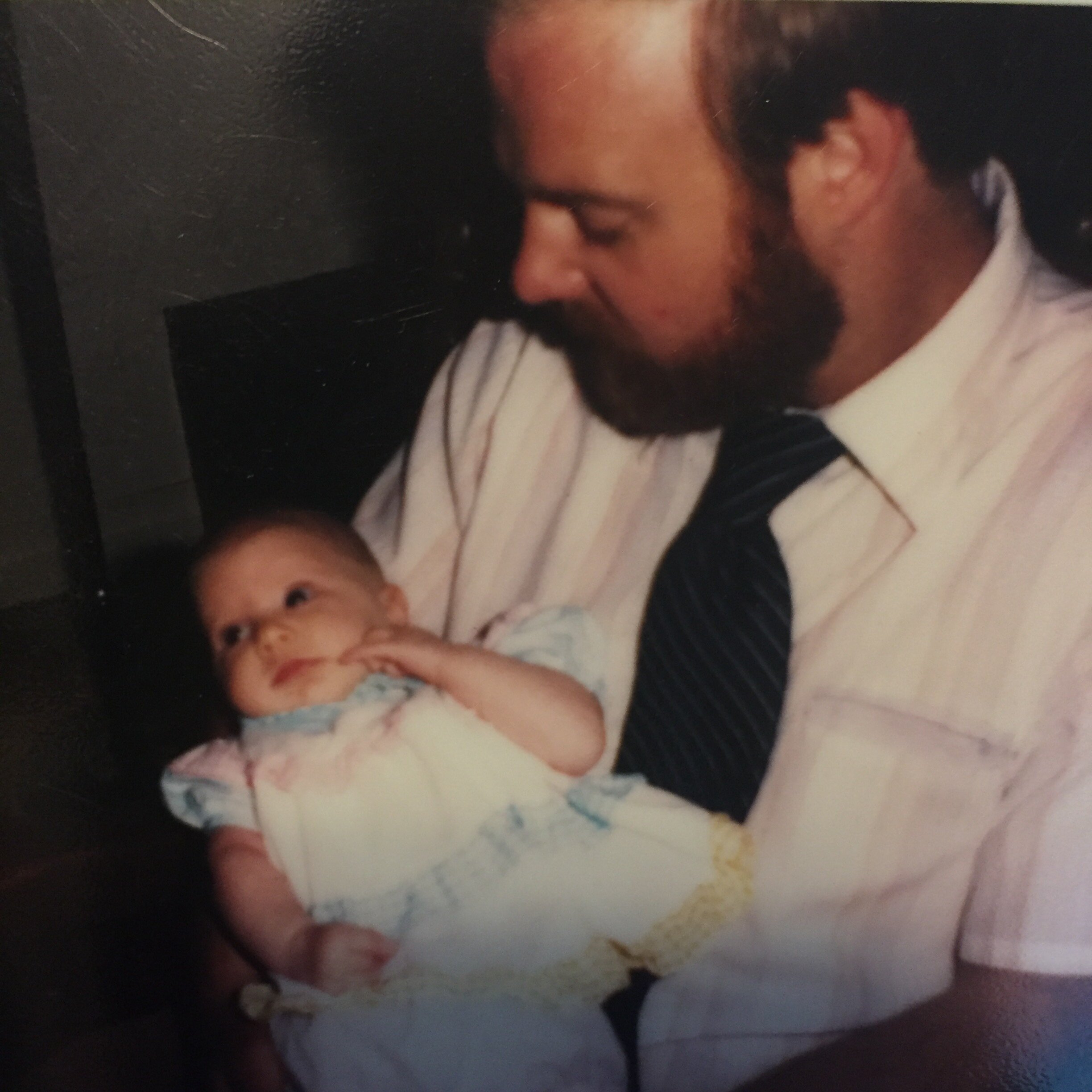

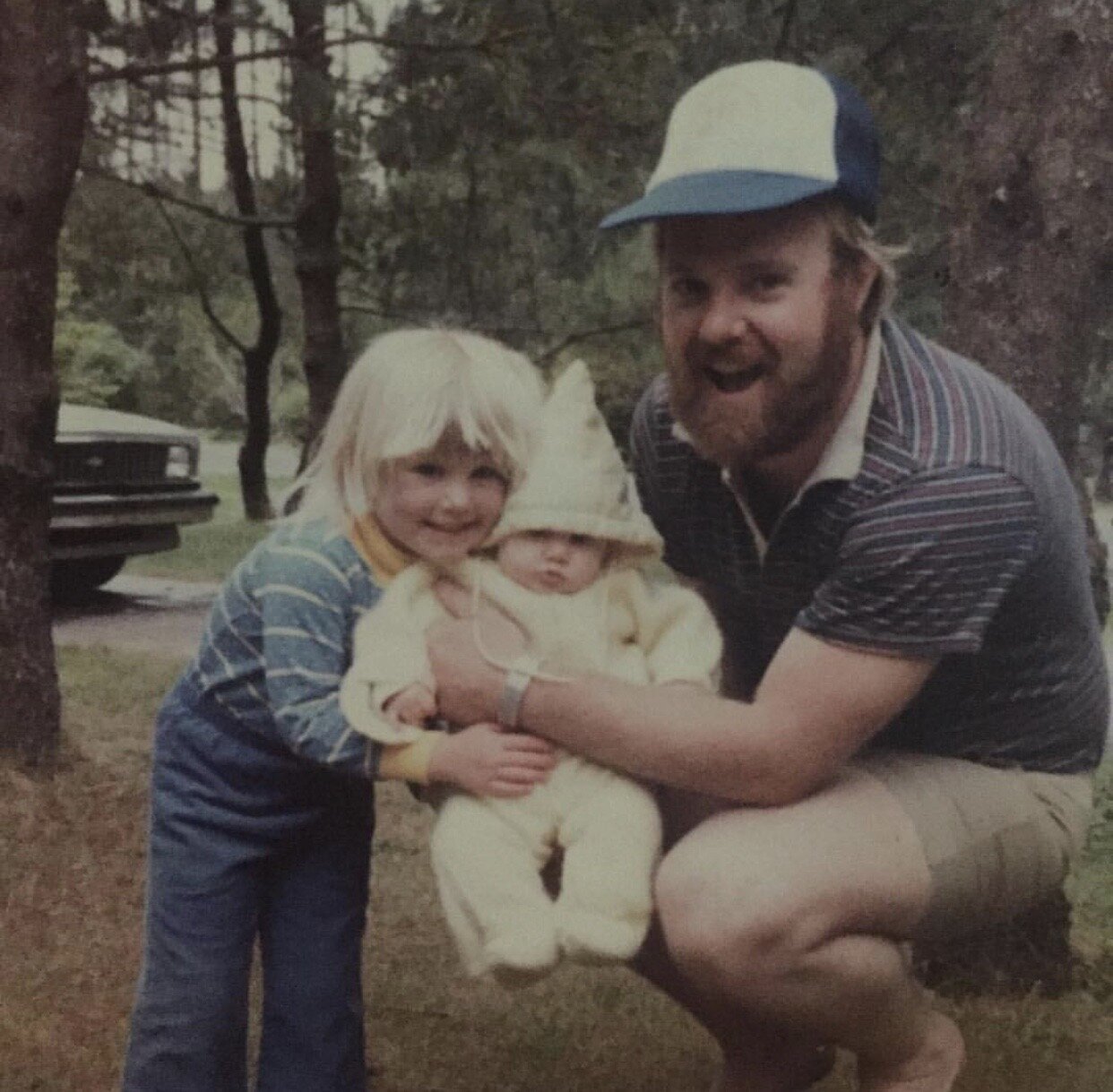

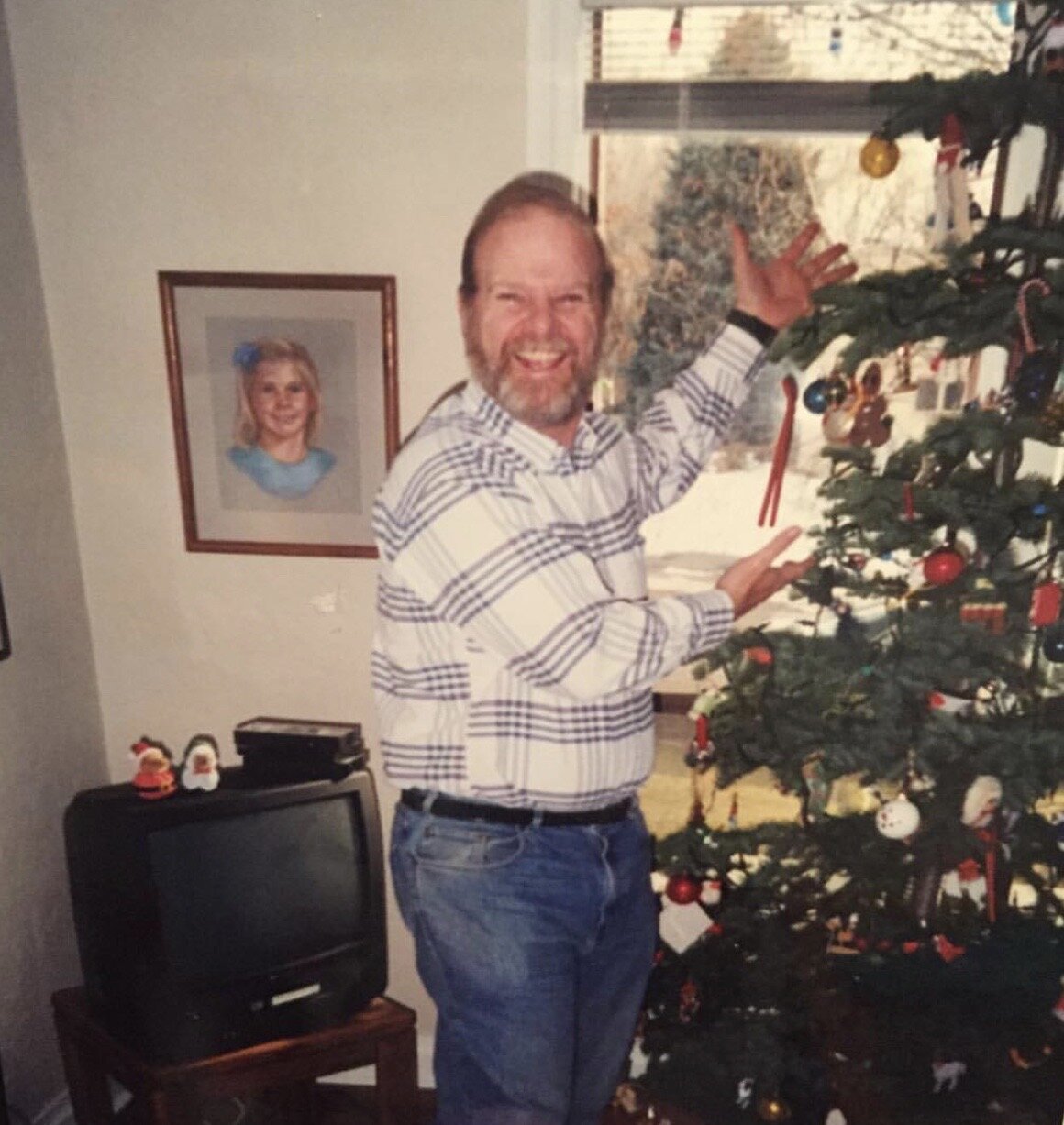

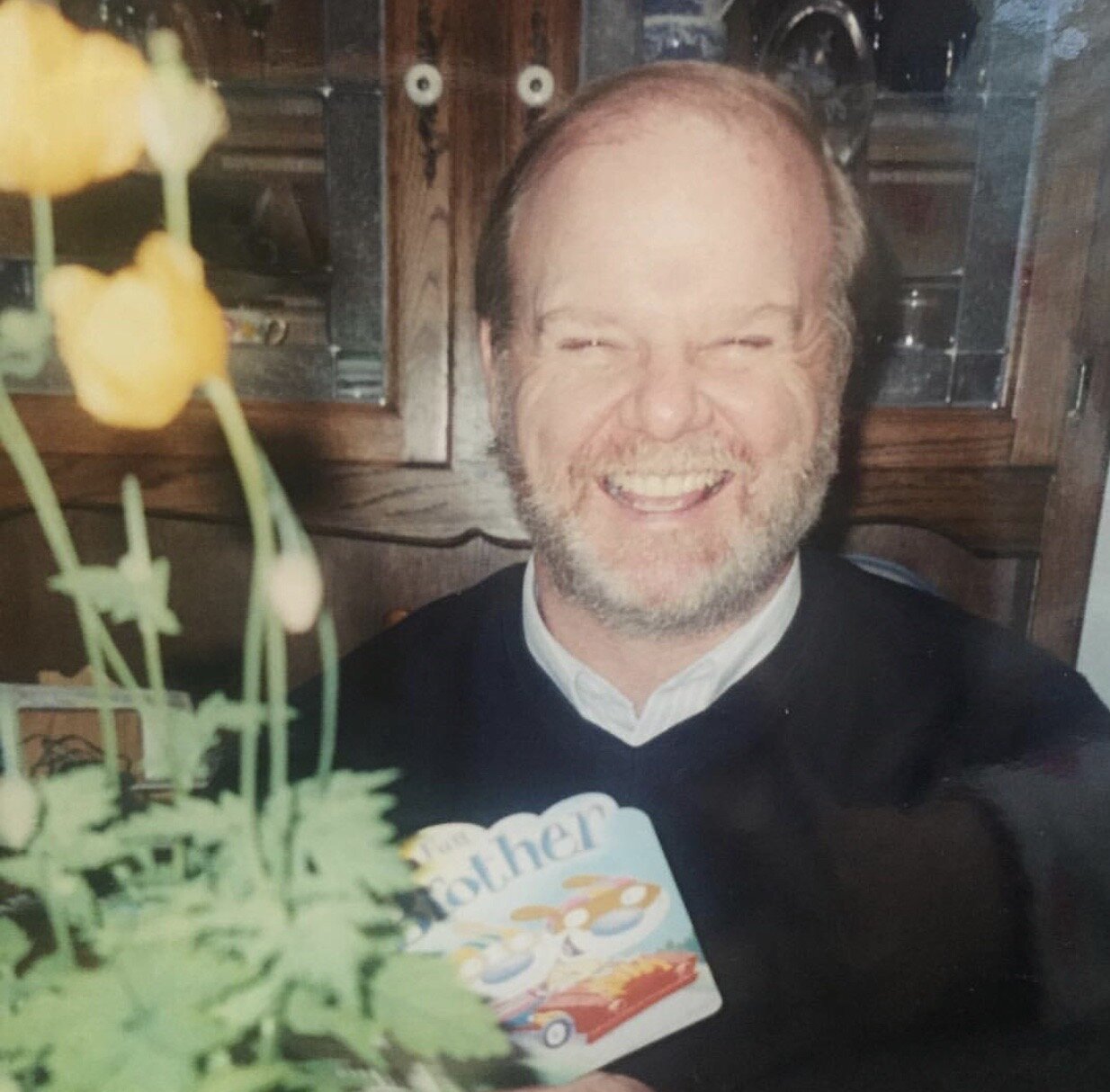

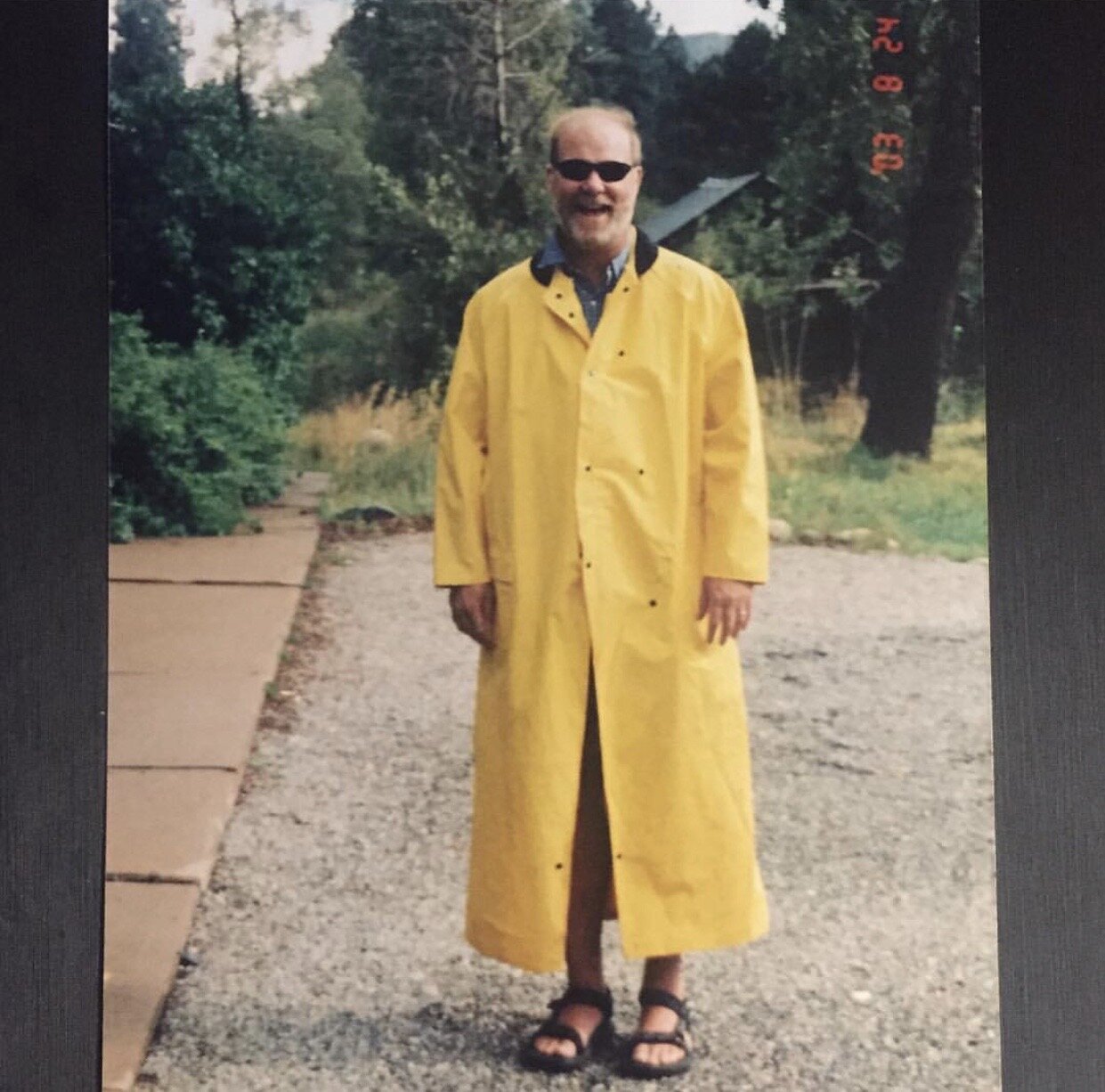

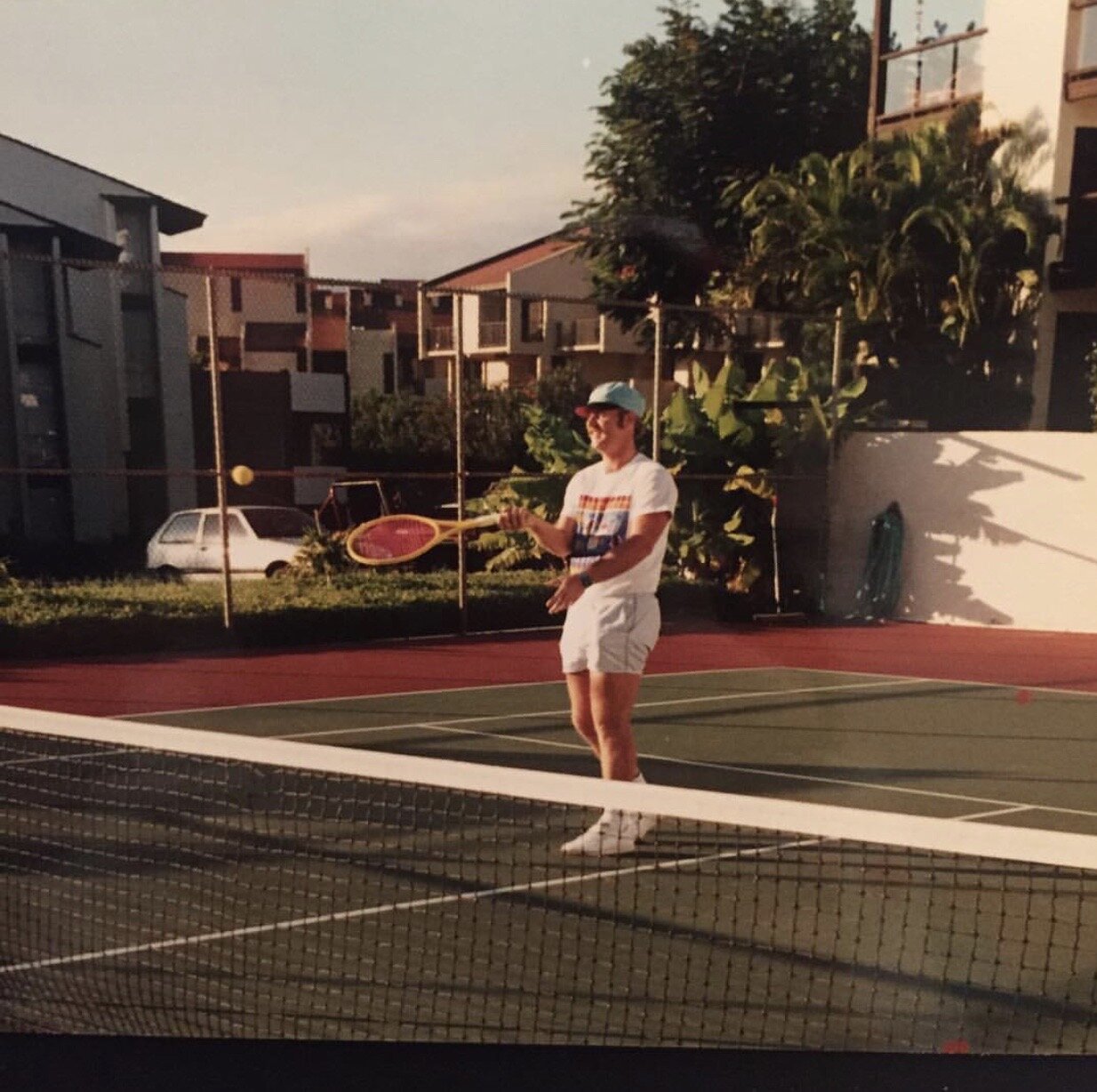

This morning I ran a virtual 5K for the Esophageal Cancer Action Network (ECAN) in honor of my dad, who died from esophageal cancer on October 13, 2018.

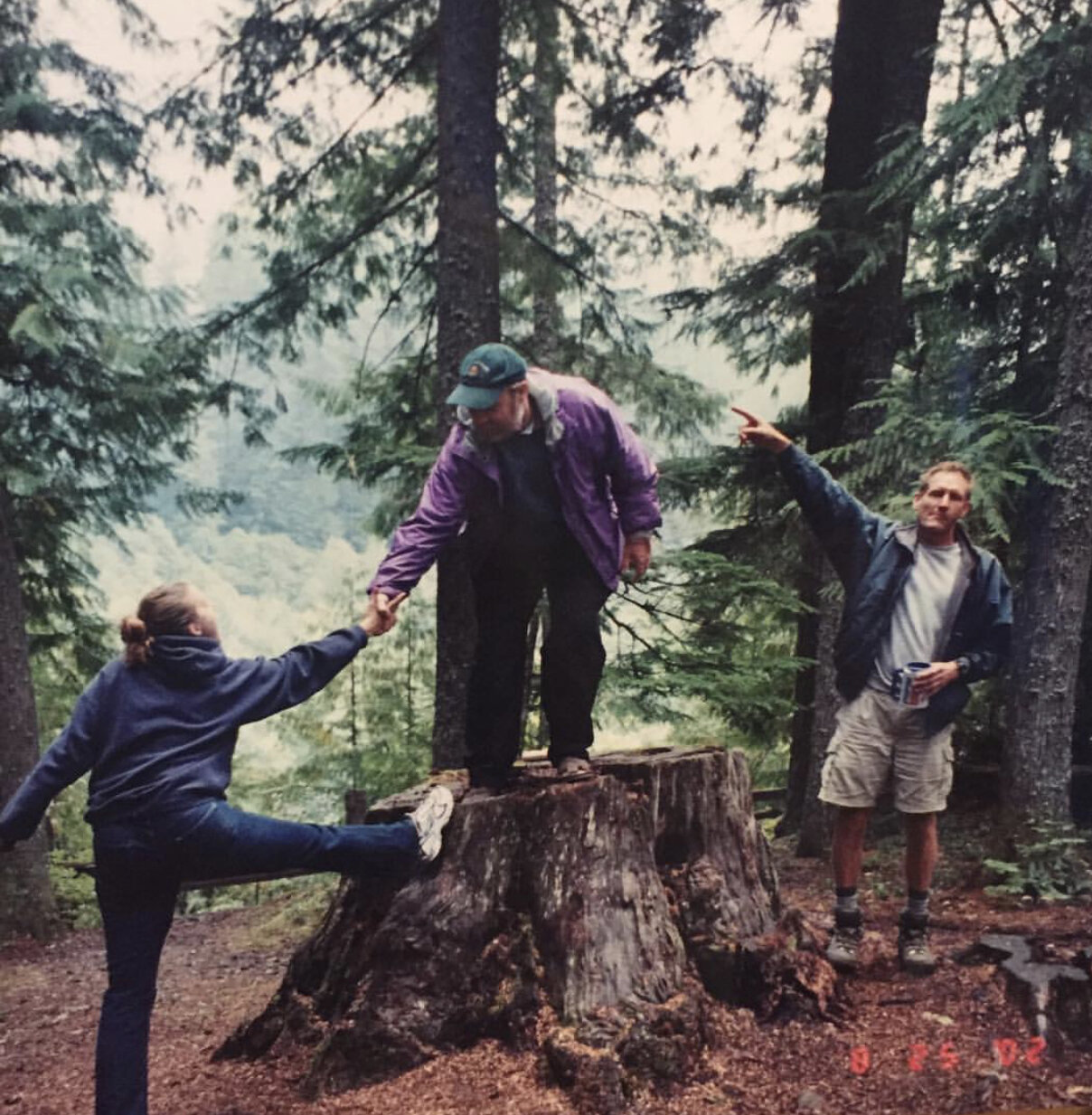

My dad used to come to all of my races — there was a period when I did a race a month, ranging from 5Ks to half marathons, for 21 straight months — and cheer me on at the finish line. I haven’t done a lot of running in the past few years. Several events converged in a short span of time: my daughter’s birth, my dad’s death, the advancement of new limitations on my postpartum body, learning to raise a child while grieving a parent, and now navigating a pandemic. Everything tumbled into each other. I rarely found the time, much less the motivation, to run.

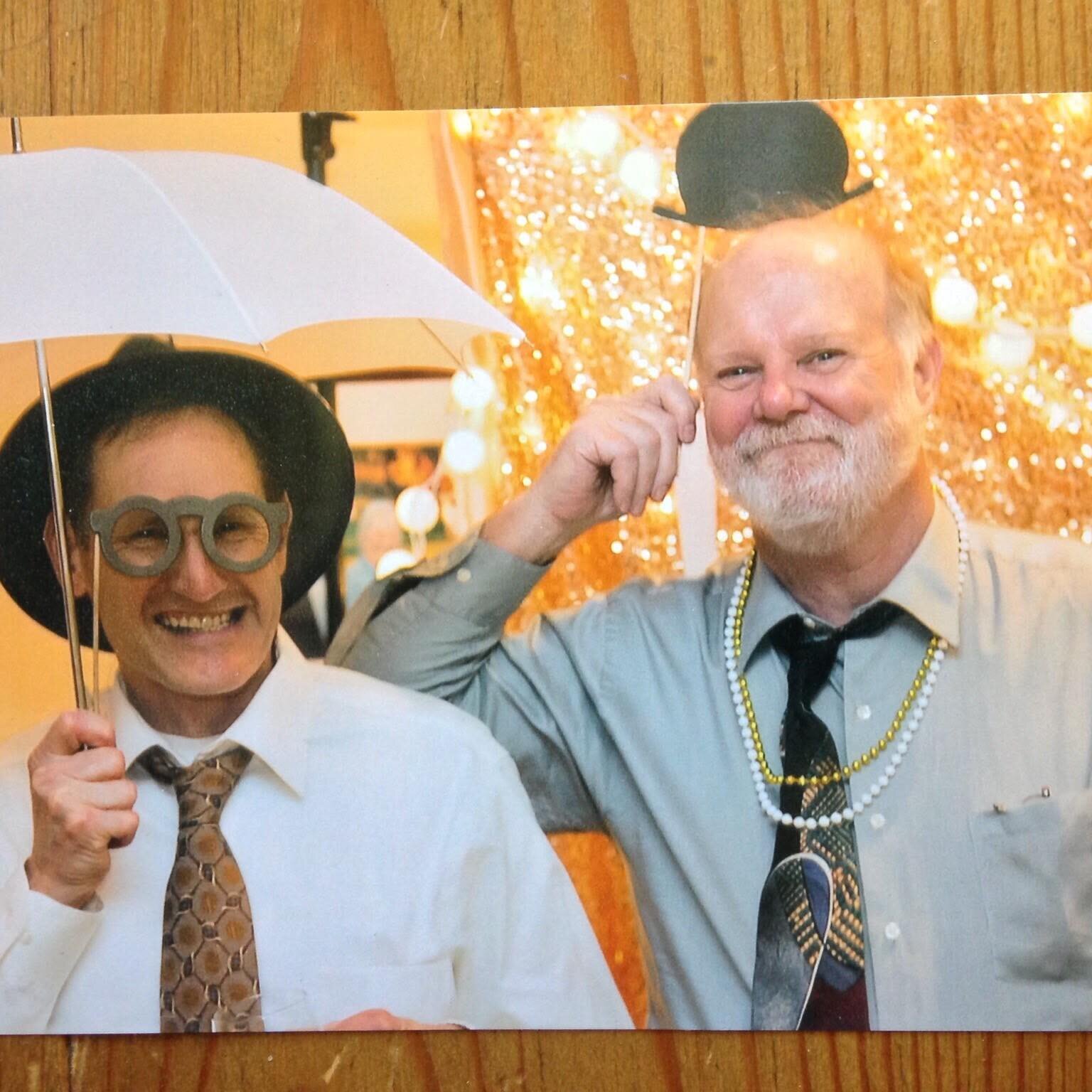

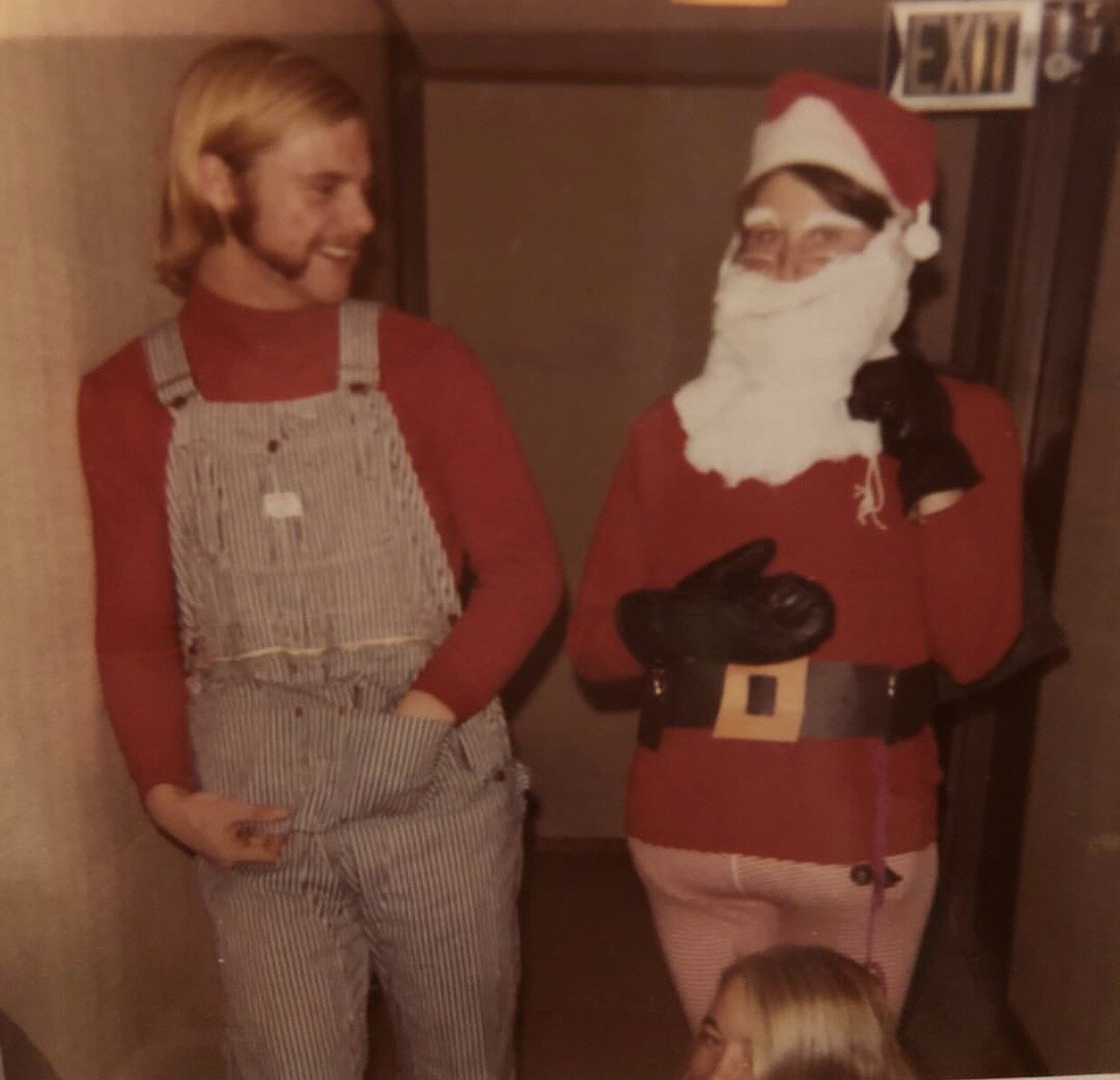

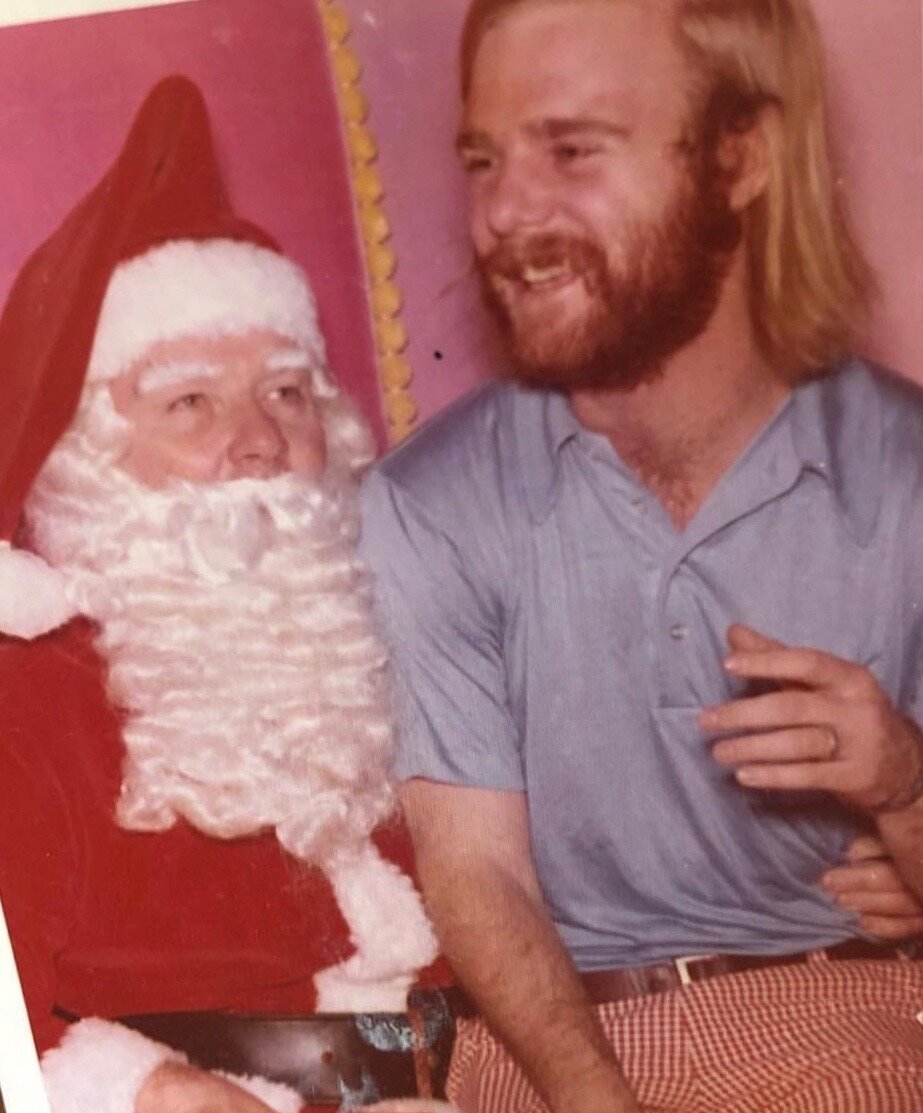

Today I had plenty of motivation as I thought of my dad during my run. It was on this day, October 21st, that my parents met at a recreational volleyball game on the CU Boulder campus 49 years ago. I know this date because my dad quoted it to me often. It was the day, he said, his whole world changed. He loved my mom the first time he saw her and he never stopped.

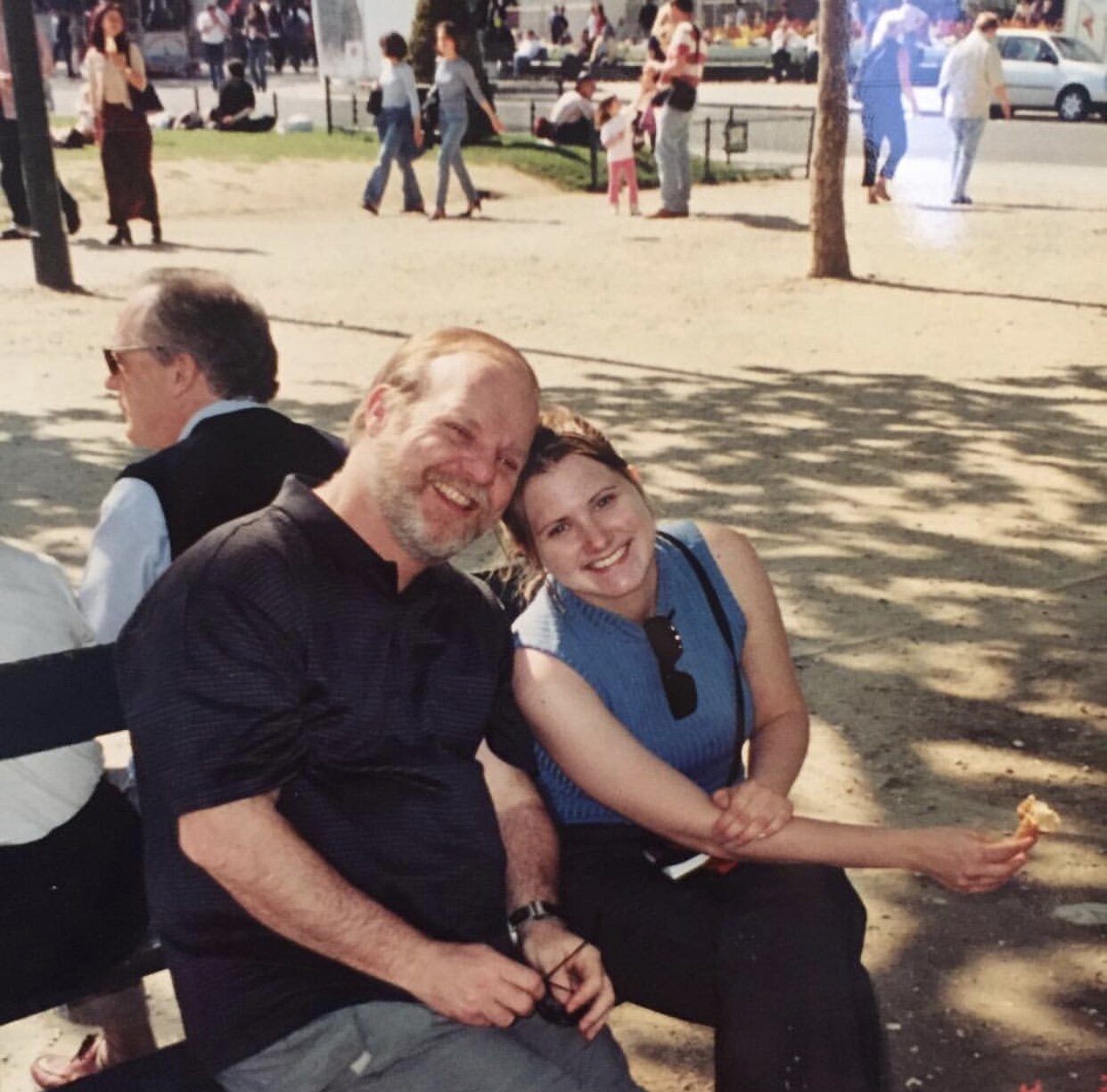

I guess this is the day that changed my whole world, too. I thought about my parents, those two college kids, as I ran through my tree-lined Portland neighborhood 1,233 miles from Boulder. I thought about my childhood and all that came before my childhood, before my sister’s childhood, when my parents were just Martin and Carolyn.

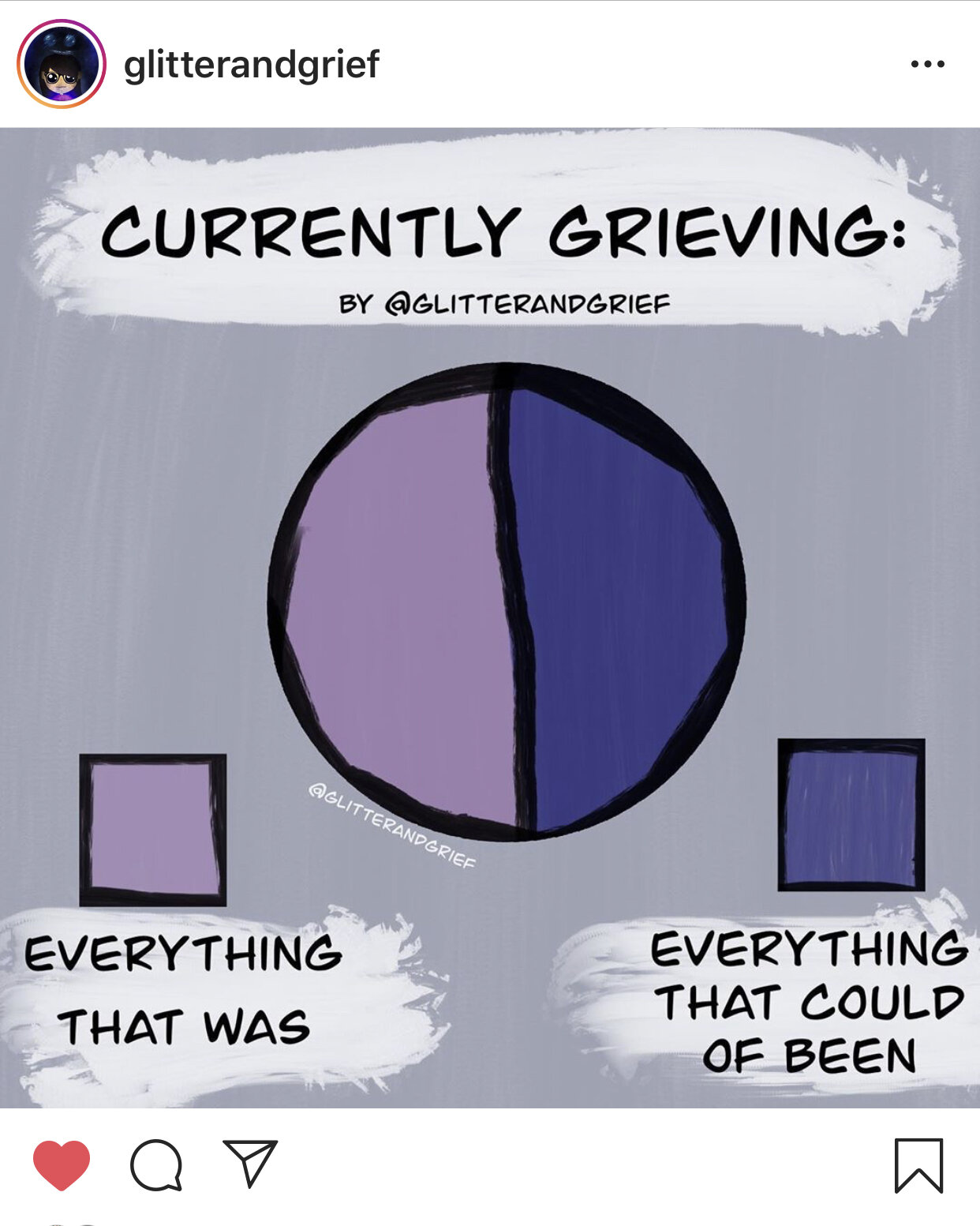

I’ve thought a lot, in the two years since my dad died, about endings. Closed chapters, shut doors.

But today I thought about beginnings. And what a lovely beginning it was.

In grief and with love,

KrissyMick

Photo Credits, Top to Bottom: Mike Daems, Unknown.