One evening when my dad was sick but not yet dying-sick, we hosted a small dinner party. Two of our guests knew other people in their lives who were suffering from the same cancer as my dad. Throughout the evening, these two guests took turns telling horror stories about their people with this same cancer: Surgeries gone wrong. Recurrences after remission. Tumors that grew too large to contain.

To this day I’m not sure what either of them was hoping to achieve by sharing any of this information. In my most generous interpretation, I wonder if they thought they were bonding with me. Like: Hey, isn’t it terrible that we all know how awful this disease is and we all know someone going through it? But it didn’t feel like bonding at all. I had to leave the room multiple times throughout the night. I tried to force myself to think of other things instead of listening to their words. Everything they were saying was horrible, but the worst part was their casual tone. They weren’t talking about people they loved. They were talking about people they were vaguely related to. They were gossiping.

They were gossiping to the wrong person. It would be like going up to a pregnant woman in her third trimester and telling her that your cousin’s teacher’s friend’s sister died while giving birth and the baby didn’t make it either, and isn’t that so very interesting? Meanwhile the pregnant woman doesn’t find it interesting at all. In fact, she is so horrified by the whole evening that after everyone goes home, and after she puts her daughter to bed, and after she tells her husband to not even think about touching her right now, she curls up into the fetal position on the faded brown couch in her living room and proceeds to scream-wail for the next four hours. The kind of desperate yell-crying that leaves a person breathless, the kind that goes on so powerfully loud for so ridiculously long that it seems like it truly might never end.

It was the kind of night that, looking back, I would classify as one of the worst of my life.

And yet, it got worse! Because months later, when my dad was no longer just sick but now dying-sick, one of these same guests was back at our house the same evening my dad was here. And this time her person with the same cancer was no longer living with the cancer, but dead. And this time she told my dad, in every breathless detail, all about his death. And my dad sat on that same faded brown couch as she sat in a chair across from him, and he quietly took all her words in. And I watched from another chair in the room, raging.

I’m still raging. We think that grief is sadness and loneliness but my grief often presents itself as a flaming ball of anger that lives inside my chest. There have been times over the past year when I’ve been unsure what to do with this fireball in my chest. The punching bag in our garage helps. Running sometimes works. Journaling. Reading. But you know what’s helped the most? Sharing my story. Not to vilify the people involved in moments like this — I know neither of our guests had malicious intentions when tossing around their careless words. But just to hear someone else say: What happened back there is terrible and I am so sorry.

Because the thing is, a lot of what happens when someone is grieving is terrible — not just because of the grief itself, but because of the things people do and say without thinking or knowing better. I can nearly guarantee you that for every grieving person you know, there are someone-said-something-that-made-me-feel-even-worse-than-I-already-do-after-losing-my-favorite-person stories that person is carrying. Comments like, “Now you can get back to your own life” from a dear family friend at the memorial service. Comments like, “I wish I lived closer — I’d come give you a hug” from a friend who lives 15 minutes away. Comments like, “Did he smoke? Did he drink a lot? Did he do [anything that might explain why HE died so I can go on feeling immortal?]”

It can be a minefield. And more often than not, the best support a grieving person receives does not come from her inner circle of friends but rather from complete strangers who have been through similar experiences. That has certainly been the case for me, with a few notable exceptions.

My dad was diagnosed with esophageal cancer when my daughter was six months old. He had a major surgery to remove his esophagus about a week after her first birthday. The combined stress of worrying about a sick parent while caring for an infant is something to be addressed in a separate post someday, but suffice it to say it’s one of the most overwhelming experiences I’ve ever gone through. My dad was in the hospital for over a week after his surgery and my basic plan was to just go every day with my baby and spend most of the time out in the hall with her, then swap with my mom and have her sit with my baby while I went in to see my dad. Hours on end, days on end, this was the plan. My husband was working, I was breastfeeding, I didn’t want to be anywhere but the hospital, and so this was the plan.

And then, on the second day there, after he came out of surgery and went to the ICU, after he was transferred from the ICU to a not-quite regular ward but not-quite as intense as the ICU ward that my dad lovingly referred to as ICU Lite, after my mom and I had done the swapping-one-form-of-caregiving-for-another switch over and over and over, my friend Kalene showed up at the hospital. She announced that she had taken some time off from work, took my baby from my arms, and told me to go be with my dad. I handed over my diaper bag, which I later realized contained ZERO wet wipes, and at some point my baby pooped and Kalene had no wet wipes and she JUST HANDLED IT. And while she was handling it, I was sitting with my dad and my mom was also sitting with my dad, or maybe my mom was eating lunch or taking a small walk, and we we were all doing things that had seemed impossible a day earlier but were suddenly manageable thanks to the generosity of my friend Kalene.

She showed up the next day and the next one, too.

You know what happened when I typed out the whole dinner party horror show? I felt the rage ball rise again in my chest. And you know what happened when I typed out the part about Kalene showing up for me, for us? I started crying. And I will probably always cry when I think about what she did for me, for us. It was so much more than I ever could have expected. It was kind and generous and helpful and NECESSARY in a way I didn’t understand until it happened — although I was making things work with the whole sick dad in the hospital + breastfeeding a baby in the hospital hallway thing, I was barely hanging on. My mom and I were exhausted. Everything felt maxed out. I didn’t even realize how dark everything was until Kalene showed up and some sunlight reappeared.

Maybe these stories aren’t helpful to you. Maybe the wrongness of the first one seems obvious and maybe the second one seems saintly, unattainable, and unrealistic. How many people could really do what she did?

Most people can not show up in such a major way. They don’t have a strong enough relationship with the grieving person to justify it. They don’t have the time in their schedule. They don’t have the inclination or the abilities to pull it off. And that’s okay.

But most people can do something. Something that meant a lot to me? Texts from a friend that said, “I’m just checking in and sending you love.” She didn’t need to offer me great words of guidance or inquire how I was doing or make a big deal of out anything. She just needed to say: I’m thinking about you.

And you know what? That little way of showing up was actually a lot more than what a lot of people did. I received a surprising amount of “I was going to come over but I know you must be overwhelmed with people stopping by” or “I wanted to cook something but I know you probably have so many people taking care of you right now” type comments, which always threw me off. Where were they gathering their information? Who were their sources? Because whatever endless stream of support coming through my house they were envisioning — it wasn’t happening quite like that.

Don’t assume everything is taken care of. Don’t ask if there’s anything you can do. Think of something you can do and do it. Maybe it’s showing up at the hospital to watch someone’s kid for a few hours. Maybe it’s sending a text to say “I’m thinking of you.” Maybe it’s offering to run an errand or do something helpful around the house. Maybe it’s writing a card. Anything is better than nothing, usually. (Granted, I would have preferred nothing to the cancer horror stories, but in general, anything is better than nothing.)

Do one little thing. To the person you’re helping, it might actually be a really big thing.

In grief and with love,

KrissyMick

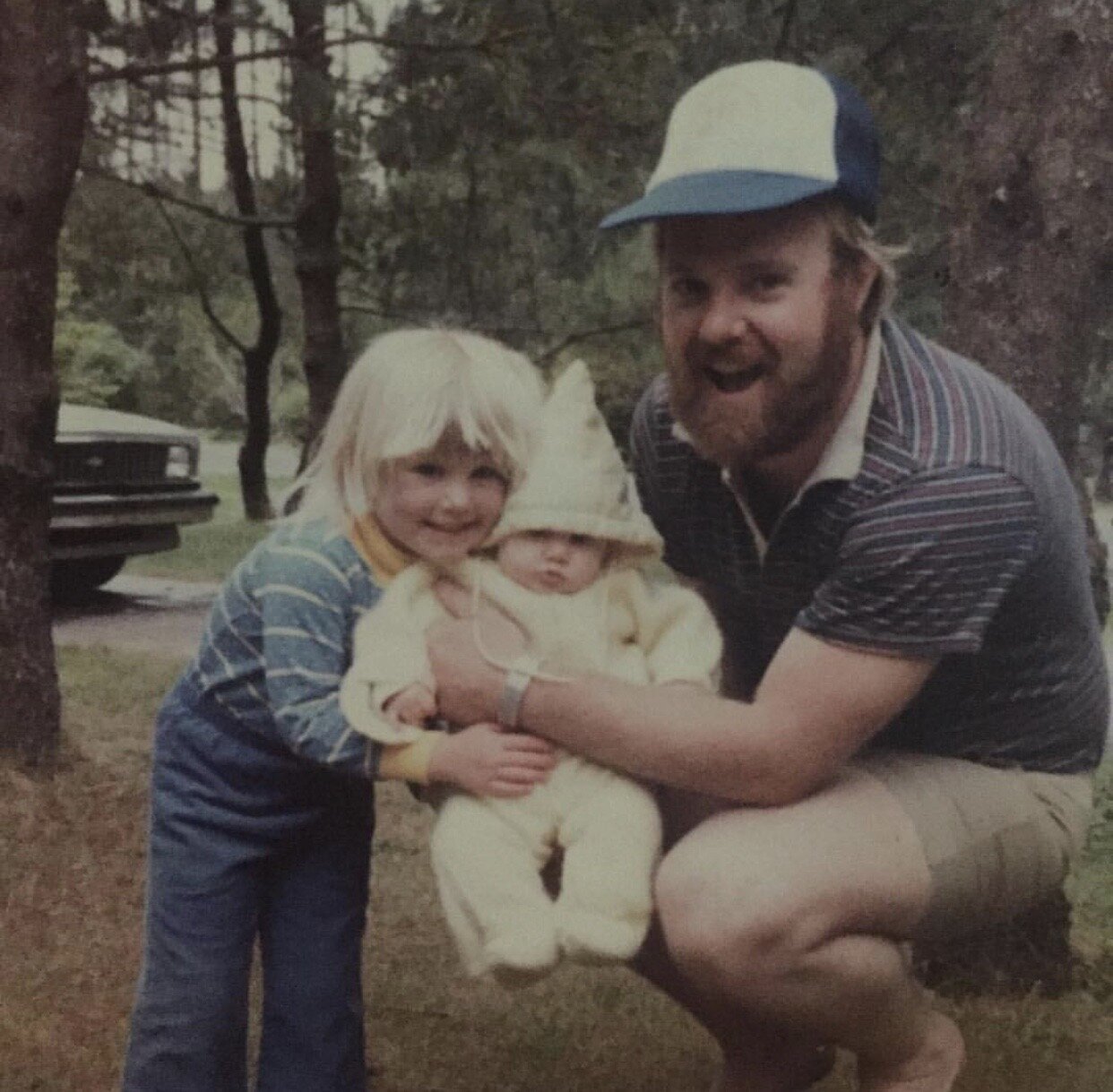

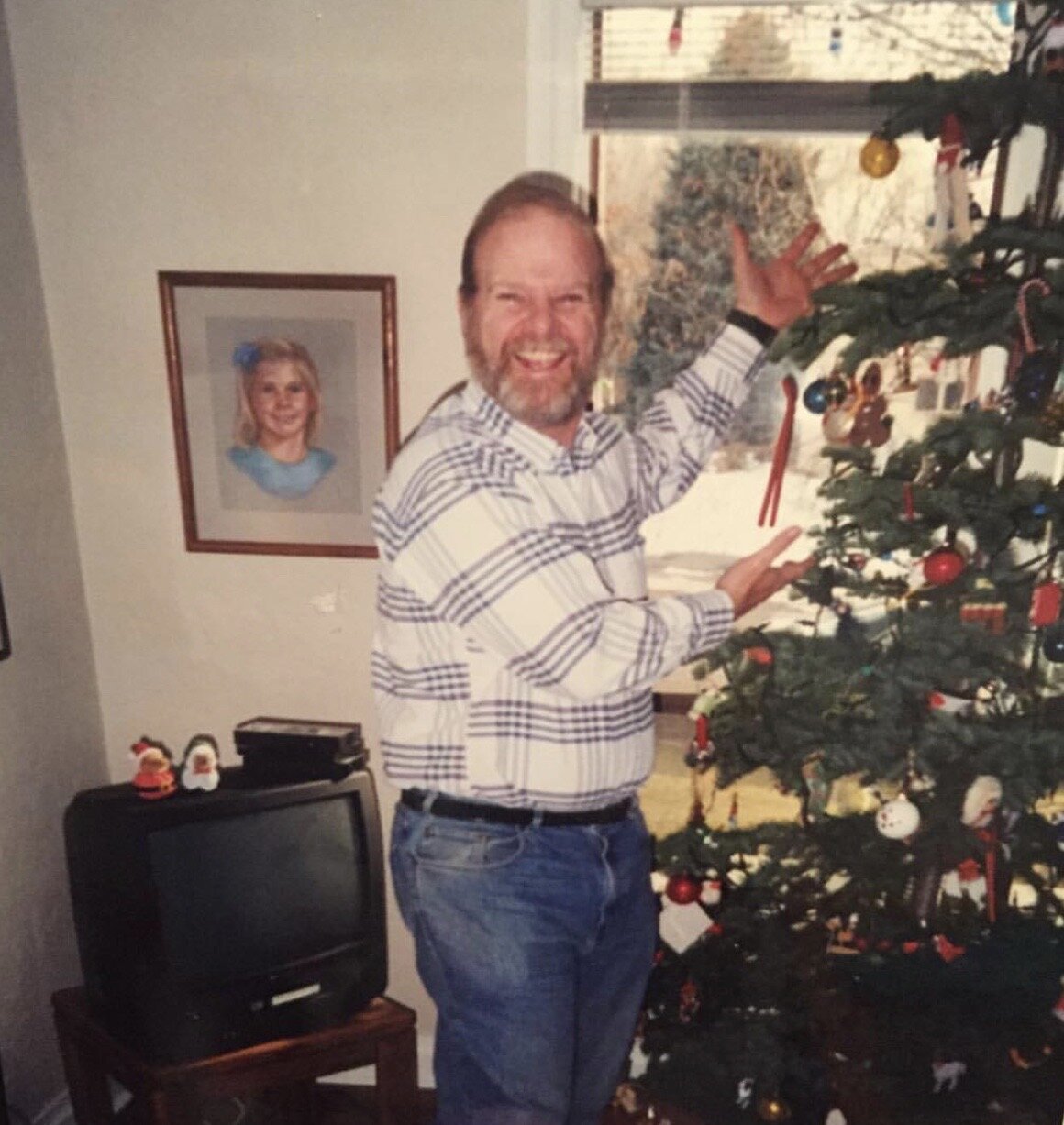

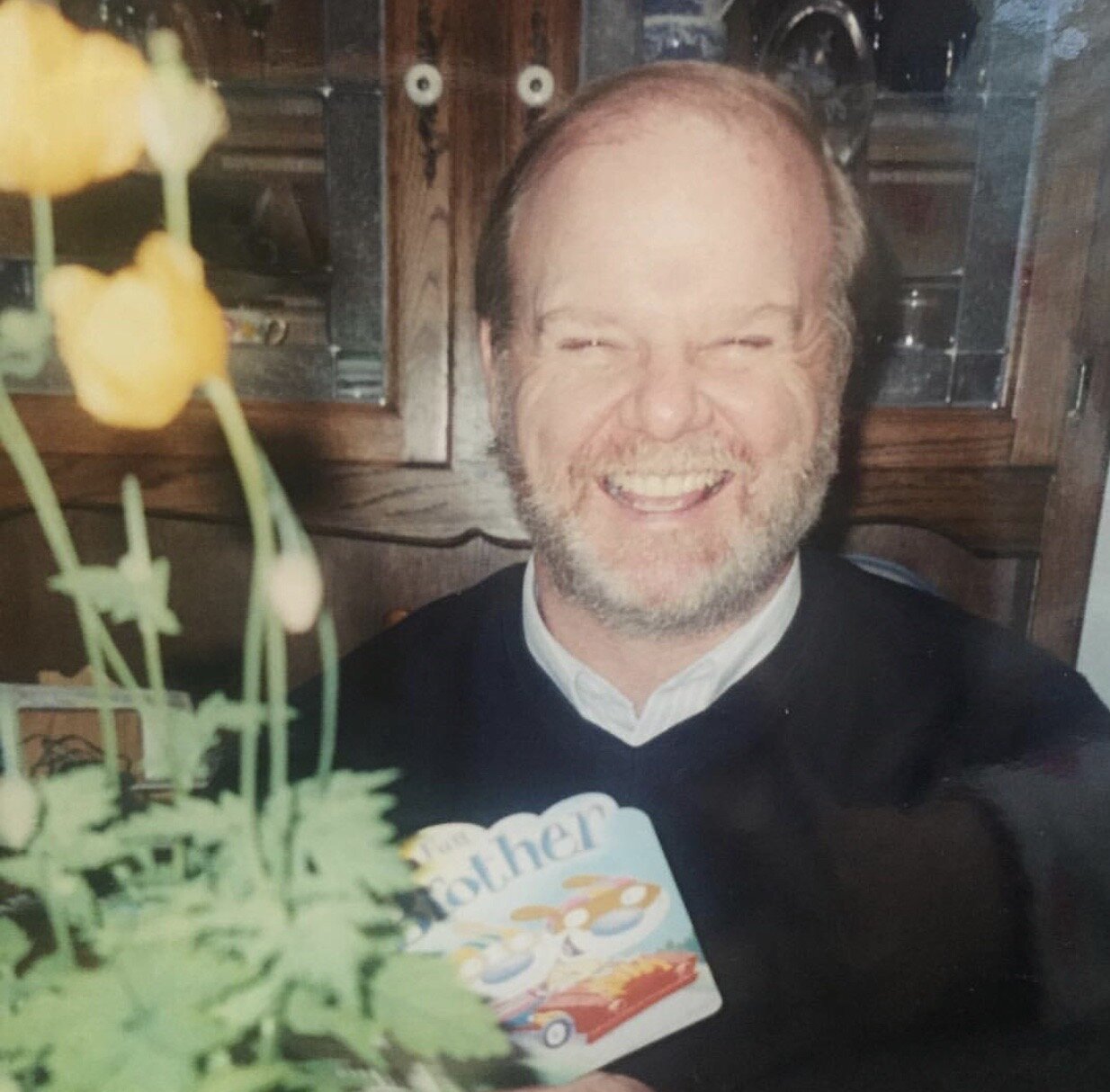

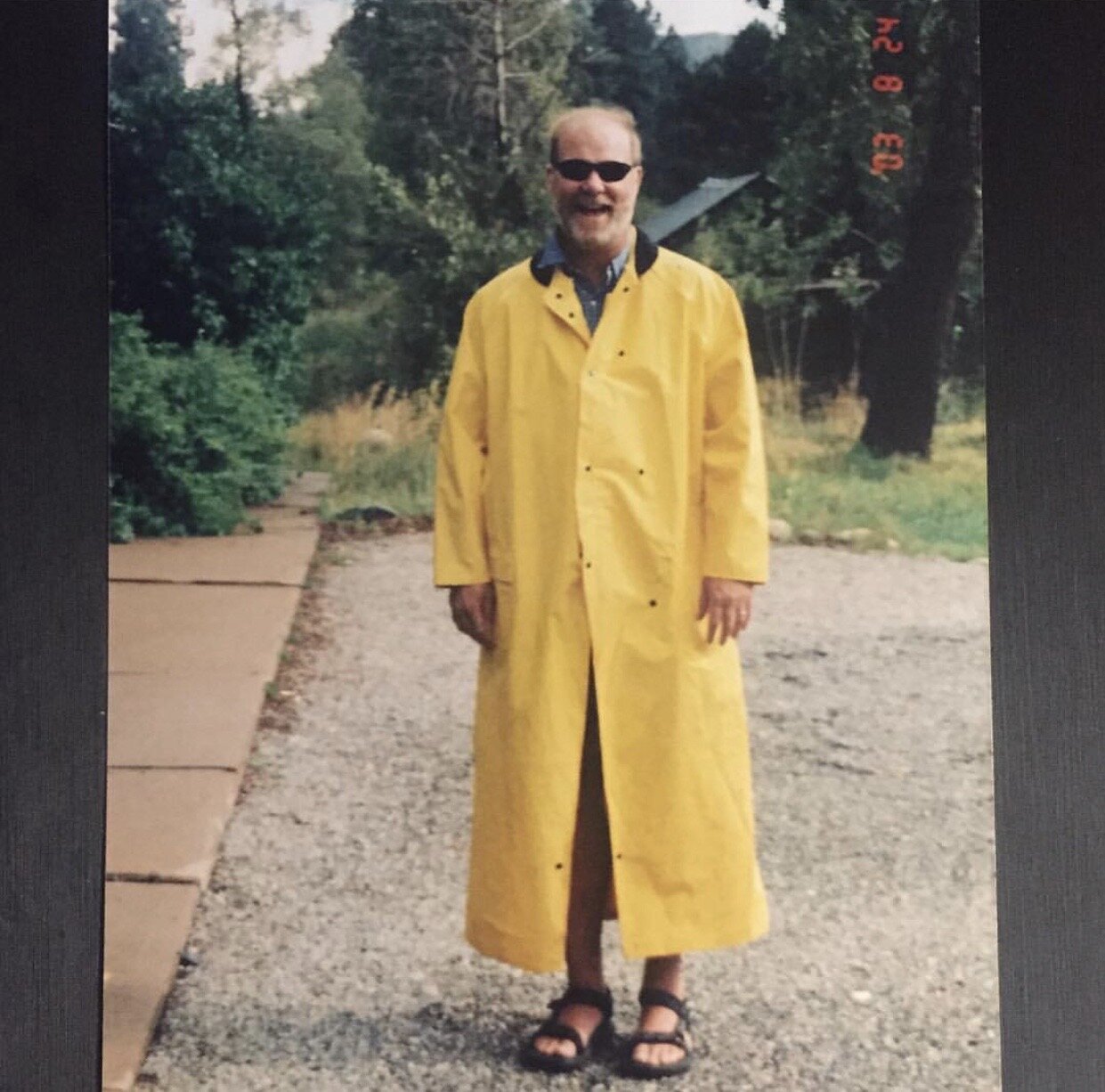

Photo Credits, Top to Bottom: Linda Lucas, Kristen Forbes, Carolyn Forbes, Carolyn Forbes, Jessica Mueller, Carolyn Forbes, Carolyn Forbes, Carolyn Forbes, Mike Daems, Kristen Forbes, Mike Daems, Carolyn Forbes, Carolyn Forbes, Kristen Forbes, Kristen Forbes